Can protecting nature and boosting the economy go hand in hand? Many people think they can’t, but new research says otherwise.

A groundbreaking study led by Dr. Binbin Li and Dr. Jingbo Cui at Duke Kunshan University has found that globally, the effectiveness of protected areas often aligns with economic growth.

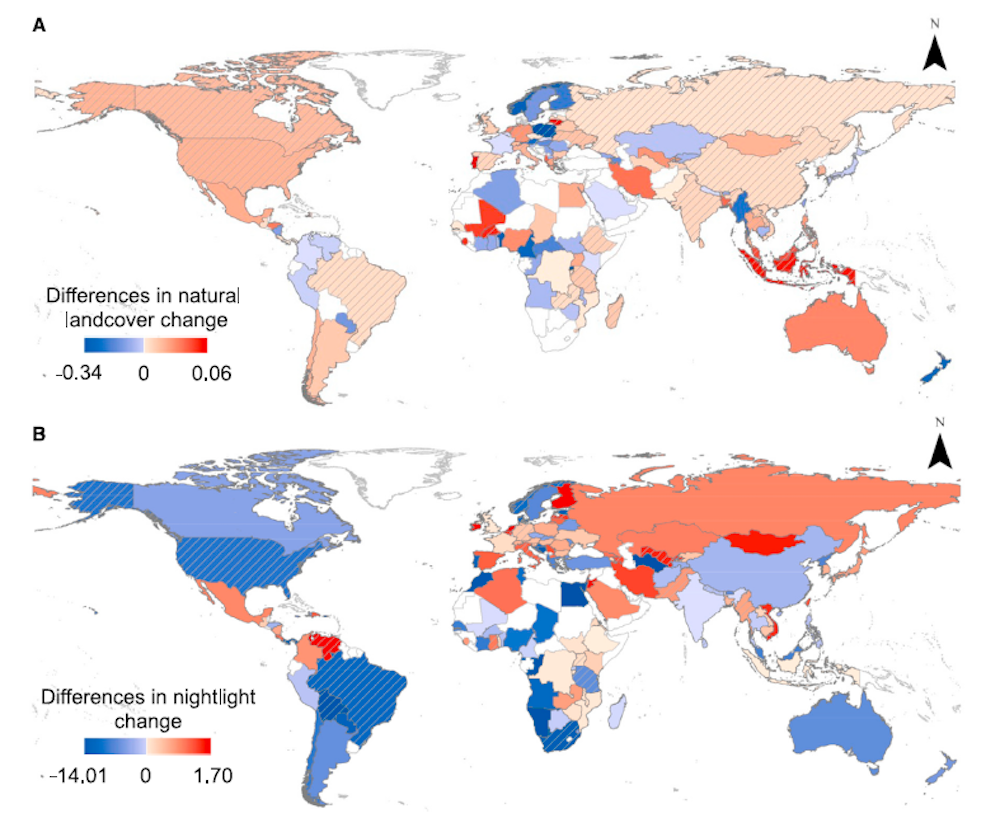

Their research shows that factors like how easily people can reach cities, the number of roads nearby, and the local economy all play a role in helping nature conservation and economic growth work together.

The study, published in Current Biology, a Cell Press journal that supports open access, is titled “The Synergy between protected area effectiveness and economic growth,” and was funded by China’s National Natural Science Foundation and the Shandong Natural Science Foundation.

Dr. Li, associate professor of environmental sciences, served as the lead author, with contributors including Jingbo Cui, also at Duke Kunshan University, Stuart Pimm at Duke University, and Shuyao Wu at Shandong University.

A global analysis of 10,143 protected areas

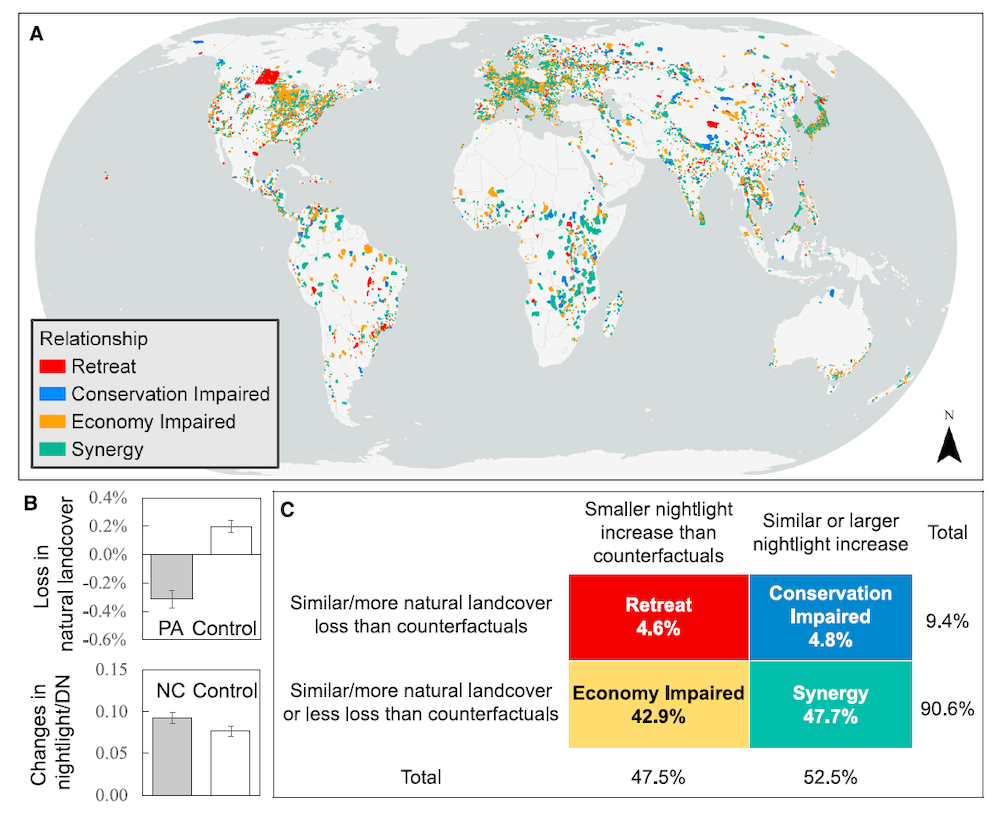

The research analyzed 10,143 protected areas and nearby communities between 2013 and 2020. It identified four possible outcomes of protected area policies: retreat, conservation impaired, economy impaired, and synergy. These can be thought of more simply as mutual loss, conservation loss, economic loss, and mutual growth. The good news? The most common outcome was mutual growth (or synergy)—where both conservation efforts and local economies thrive.

However, the study warns that in countries with weaker economies, protected areas are more likely to suffer mutual loss, where both biodiversity and local economies decline. This highlights the importance of addressing poverty when creating conservation strategies.

Bigger isn’t always better

Interestingly, larger protected areas don’t always guarantee better results. As protected area size increases, the likelihood of mutual growth decreases—especially in developing countries. The research also found that conservation and economic growth work best together in temperate forests, with grasslands and deserts coming next.

What’s next for conservation?

Li explained that as it becomes harder to expand protected areas, smaller, well-managed reserves in densely populated regions might offer the best path forward.

“Our findings overturn the old belief that conservation must come at the expense of economic growth,” she said. “They show that protected areas and economic prosperity can reinforce each other.”

“By combining environmental science, economics and big data,” Jingbo Cui added, “we aim to provide policymakers with tools to foster both conservation and economic development.”