Each year, DKU undergraduates step beyond the Kunshan campus and spend a semester studying at Duke— diving into new environments, new questions and new possibilities. Our DKUers at Duke series follow these students as they explore another academic home and see the world through a wider lens. This is one of those stories.

Learning nature’s language

The morning air in the mountains outside Beijing carried the scent of pine and damp earth. As sunlight filtered through the trees, a young boy adjusted his binoculars, ready to capture another moment of life in the wild. That boy was Charles Yan.

As a child, he could spend hours watching BBC documentaries, the soft light flickering across the room. On screen, whales breached, leopards slipped through the shadows and even the loneliest deserts pulsed with life. While other children preferred cartoons, Charles was already learning the rhythms of the natural world.

“Back then, I didn’t realize how that early curiosity was quietly shaping my life,” he said. “I just kept watching documentaries and reading books.”

But his fascination never stayed on the screen. Many weekends began before sunrise, when Charles and his family packed binoculars and snacks before driving two hours into Beijing’s surrounding mountains. They chose the wilder trails — routes tangled with roots, rocks and signs of wildlife.

“As a kid, I wasn’t really looking for birds,” he said. “I liked things I could touch, like plants and insects.”

Charles’ mother — his earliest supporter — soon noticed the spark in her son. She signed him up for summer programs run by Friends of Nature, China’s first nationwide environmental NGO. In Liaoning, Taiwan and the Wuyi Mountains, Charles explored the diversity of China’s landscapes and deepened his sense of wonder.

After high school, his curiosity carried him beyond China’s borders. In Tasmania and mainland Australia, he stood on cliffs carved by crashing waves. On Indonesia’s Komodo Islands, he watched giant Komodo dragons lumber across the sand — living reminders of an ancient world. In Nepal, he explored forests protected through national conservation programs and Indigenous stewardship.

“I’ve learned to value everything that isn’t human,” he said. “The world is so beautiful, and I don’t want to lose it.”

Turning curiosity into scientific practice

When Charles arrived at Duke Kunshan University, choosing his major felt effortless. Environmental science wasn’t a decision; it was the continuation of a story he had been living for years.

During his freshman year, he joined a giant panda conservation project supervised by Dr. Binbin Li. His task was to sort thousands of motion-triggered camera images from Sichuan and identify wildlife species to support ecological monitoring. The repetitive work only drew him in further.

“That was when I realized what wildlife research really involves,” he said. “Patience, precision and learning to understand a forest that never speaks.”

Later, Charles discovered a part of nature he never expected to love: birds. As a child, they had felt distant — beautiful but unreachable. That changed when he joined Prof. Jimmy Choi’s waterbird ecology group. He began studying migratory shorebirds and the invertebrates they feed on in intertidal wetlands — ecosystems fragile and heavily shaped by human activity.

In Lianyungang, where wetlands once faced threats from entertainment-related development, Charles collected and examined invertebrate samples under a microscope, tracking how the landscape recovered after disturbance.

“Our long-term monitoring showed that recovery was slower near construction sites,” he said. “But nature always tries to take back what belongs to it.”

A new chapter at the Duke Marine Lab

While Beijing’s mountains and DKU’s labs nurtured his love for wildlife, the ocean transformed it during his exchange semester at the Duke Marine Lab in North Carolina. His first moment there felt unreal. As he stepped out of the car and looked up, a pelican glided across the sky.

“I grew up in the city,” he said. “Seeing a pelican fly overhead felt like stepping into the documentaries I watched as a kid.”

The Marine Lab, tucked on tiny Pivers Island, feels nothing like Duke’s main campus. Instead of crowded dining halls and city noise, Charles studies in ground-level classrooms where days begin with lectures on marine life and end with kayaking trips to nearby islands. What fascinates him most is the accessibility of the faculty.

“I normally rely on email,” he said. “But the Marine Lab is small and collaborative, so I found myself knocking on doors more often to ask about research, and they’ll say, ‘Of course.’”

Their openness made courses feel personal. One class, Sensory Physiology of Marine Animals, taught by an 80-year-old professor who had spent a lifetime studying marine environments, became unforgettable.

“It felt like learning science through someone’s lived history,” Charles said.

A dream realized in the Galapagos

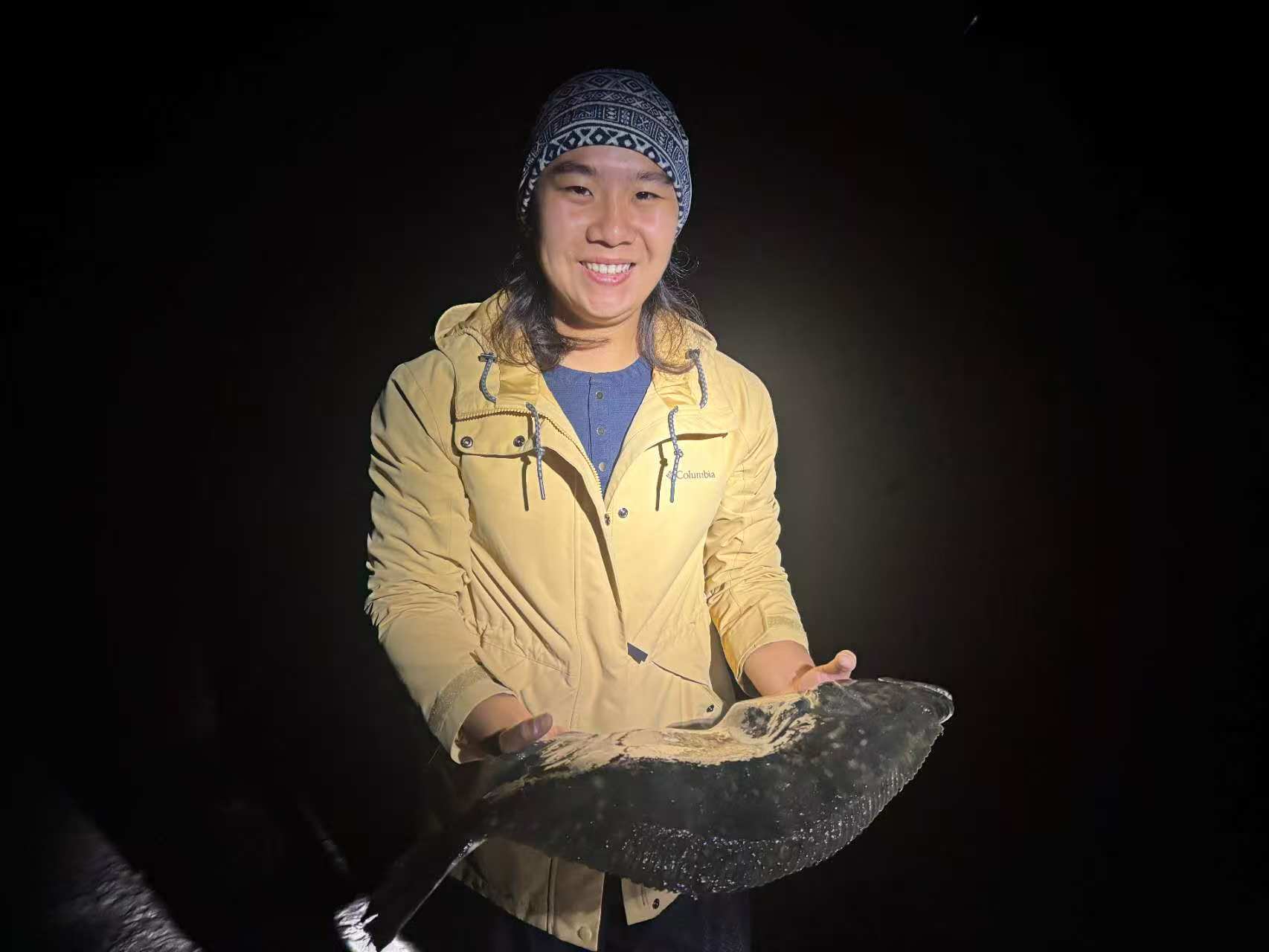

That sense of wonder followed Charles to the Galapagos Islands, a place he had only dreamed of visiting as a child.

“When I was young, it felt impossible,” he said. “Too far, too expensive. And suddenly, I was studying at the local university and going on field tours with researchers.”

Through the Duke Immerse program, he and his classmates studied water resources, renewable energy, food transportation and conservation policy in the Galapagos. Guided by local scientists, Charles saw endemic species up close — creatures found nowhere else on Earth.

“It felt surreal,” he said. “The animals I saw on screen were right in front of me.”

In a world transformed by climate change and rapid development, the experience reminded him that conservation is never out of reach — it depends on people and the choices they make.

“There are solutions,” he said, “but they only work when those with power and resources are willing to care.”

Carrying responsibility into the future

Now, Charles hopes to carry these lessons into his Signature Work. He originally planned to study the migration strategies of shorebirds, but nearby construction may require him to change direction. He is now considering how human activity reshapes bird behavior, movement and survival. Ultimately, he hopes to become a wildlife conservation researcher — someone who studies ecosystems and helps protect them.

“I want to do meaningful work in conservation,” he said. “And I want to broaden my view beyond a single project to understand the world as a whole.”

Every place he has been — and every lesson he has learned — has shaped how he sees the living world. From the mountains of Beijing to the shores of North Carolina and the islands of Ecuador, Charles’ journey has taught him that loving nature is both a privilege and a responsibility.

“I wish more people understood,” he said, “that wildlife’s beauty isn’t just something to look at — it’s something to honor. Every bird and every butterfly carries the story of evolution in its wings. You just have to look closely enough to see it.”

By Anastasia Titarova, Class of 2027