Binbin Li, assistant professor of environmental science, is a leading figure in wildlife conservation in China

By Chenling Qu

Student Media Center fellow

Binbin Li slowly looks up to the sky as she searches hard for an answer. I’ve just asked about her most challenging experience out in the field, expecting to hear a tale of adventure tracking wild giant pandas in the forests of southwestern China. To my surprise, she’s stumped.

‘I really don’t have those kinds of stories,’ she says. ‘I think I’ve been lucky.’

‘Lucky’ is a word that crops up a lot in my interview over dinner with Li, assistant professor of environmental science at Duke Kunshan and a leading figure in wildlife conservation in China. She uses the word when talking about finding her passion at a young age, about meeting the people who inspired her to follow that passion, and about finding success in a male-dominated field that requires carrying out research in grueling conditions.

A more suitable replacement would be the word ‘tenacious.’

‘Wild panda habitats are among the most difficult places for fieldwork compared with anywhere else in the world. The weather is unpredictable,’ she says, explaining that the forests of southwestern China see a lot of rain, making conditions cold and slippery.

‘But if you like this work, then you’ll know it’s all part of nature. When you love something, you won’t be so picky. You’ll be easily satisfied, even if the conditions are pretty basic.’

Li with a panda cub at Beijing Zoo

Li has been conducting field research since 2007. Her most recent expedition took her to the proposed Giant Panda National Park, where she spent three months studying the impact of grazing on the habitats of giant pandas and other rare species with colleagues and students from Duke Kunshan.

After seeing her climb mountains and hike long distances for her work, often outpacing male colleagues, fellow researchers nicknamed Li ‘Bin Ye,’ a respectful title that recognizes her physical and spiritual strength.

However, despite her skill and reputation, she says a major challenge remains in changing people’s preconceptions about a female wildlife researcher.

Dealing with people’s first impression of her is difficult, she says, explaining that at the start of each new field project, she will tell someone she wants to go somewhere remote and they will reply, ‘But you won’t be able to get there.’

‘This just comes from their first impression of me. They think, ‘You can’t do that.’ Even those who know the name Bin Ye, they may think it’s just a nickname that means nothing. They won’t think it means this is a strong person in the field. Naturally, they think you’re not capable of getting there. If I was older, a man with a beard, and looked tough, then people may not have that impression.’

Rain and hard terrain are things you can prepare for on a research trip, but people’s assumptions are more unpredictable. ‘It’s actually the biggest obstacle I’ve faced,’ she adds.

Li came across similar prejudice in her college years.

A native of Beijing, Li earned a bachelor’s degree from the prestigious Peking University in 2010 before heading to the United States to obtain a master’s in natural resources and environment from the University of Michigan and a Ph.D. from Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment.

Li carries out field research at Wanglang National Nature Reserve, Sichuan province.

At her high school, girls would always outperform their male peers, she recalls. ‘There was never a doubt that girls were equal to boys ‘ in fact, we might even have thought we were better. You never expect some people might think differently.’

Li spent a large part of her childhood in her parents’ rural hometown and developed an interest in animals, insects and other wildlife at an early age. Yet when she declared her interest at college to major in conservation biology, an area that requires extensive field research, she came across many people who doubted she could do it.

‘Several people said to me that girls are not suited to this, that there was no hope for conservation at all. Their negative attitude wasn’t just toward women but the entire research area,’ she says, adding that it was tough blow to discover that conflict between ideality and reality.

Did she think about giving up at that point? ‘The thought never escaped me,’ she says. ‘But I was lucky. Every time I began to have this thought, there was someone there to help me. It’s really important sometimes that a small piece of advice comes just at the right time.’

One of the most important interventions came from a guest speaker at Peking University, Peter Raven, a leading botanist, who told her to ignore the doubters and follow her passion.

She describes such advice as ‘a light in front of you,’ something to work toward, and says that it’s one of the reasons she decided to join Duke Kunshan, to be able to provide encouragement to her own students. In addition to being a faculty member in the international master of environmental policy program, Li also teaches an Intro to Environmental Science course in the undergraduate program.

For those worried about prejudice and preconceptions in their chosen field, particularly her female students, she has one simple piece of advice: Actions speak louder than words.

‘Ask yourself, ‘What can I accomplish here?’ Sometimes women just have to do things and show people. That’s the way I work,’ she says. ‘Just do what you need to do. It’s all about your attitude. There are more solutions than problems.

‘You need to have hope. Otherwise, before you actually reach a solution, you will just stop.’

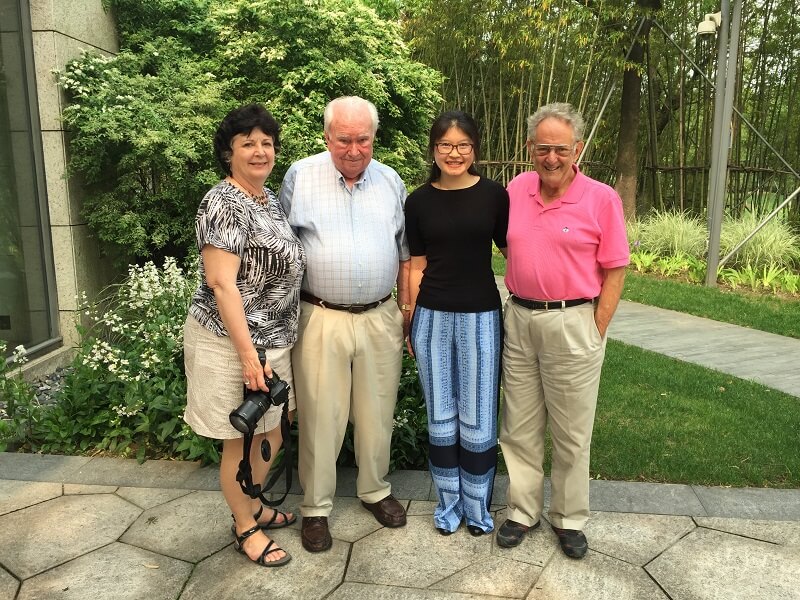

Li poses with botanist Peter Raven (second left), his wife Pat, and influential wildlife conservationist Stuart Pimm.

Away from academia, Li is also lighting the way for conservationists through her work as a nature photographer for Swild, a nature photography and film organization based in China. She was also an adviser on the Disney documentary ‘Born in China’ and is co-founder of Duke Story for Nature and People, which promotes scientific communication through multimedia.

Li says finding your true passion is crucial. She originally studied environmental science at Peking University before realizing her interests were in conservation biology, in particular wild animals, which resulted in her transferring to a different major in her sophomore year.

‘A lot of young people want to find their dream right away. They want to try one time and know something’s for them. But you have to try many times, and many different things,’ she says. ‘If you really have passion, you can always make it work.’

After dinner, Li and I say our goodbyes and I’m left with one thought: Talent, hard work, optimism, opportunities, a good support system, these are all just firewood. Passion is the spark that allows a leader in his or her field to light the way for others.

Chenling Qu, undergraduate Class of 2022, is a fellow at the Student Media Center.

A photo by Li of Tibetan antelope at the Changtang Nature Reserve in Tibet