When a Buddhist monk claimed the Buddha understood the solar system 2,500 years before telescopes, most people would close the book and move on.

Ben Van Overmeire at Duke Kunshan University did the opposite.

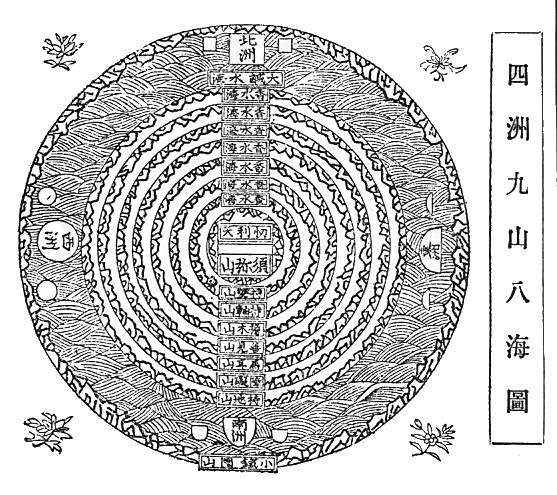

While reading a volume on Buddhism and science, he came across a chapter on traditional Buddhist cosmology—the old vision of a flat earth with a massive mountain, Mount Sumeru, rising at its center. The author explained how most modern Buddhists quietly set that image aside as Western astronomy spread through Asia. The world, they accepted, is round. The mountain is metaphor.

Then came a throwaway line: “Some people imagined Mount Sumeru in outer space.”

“That one sentence stopped me,” said Van Overmeire, assistant professor of religious studies. “I thought, who on earth said that? Who would put this ancient cosmic mountain into space?”

He emailed the author. The author no longer remembered.

“That’s when something very weird grabbed my imagination,” he said. “And usually, that’s where my research starts.”

From a single odd remark in a footnote, a research project was born.

A monk, a mountain and a solar system

Van Overmeire’s current work sits at the intersection of Buddhist studies, intellectual history, and what scholars now call “astroculture,” the cultural imagination surrounding outer space.

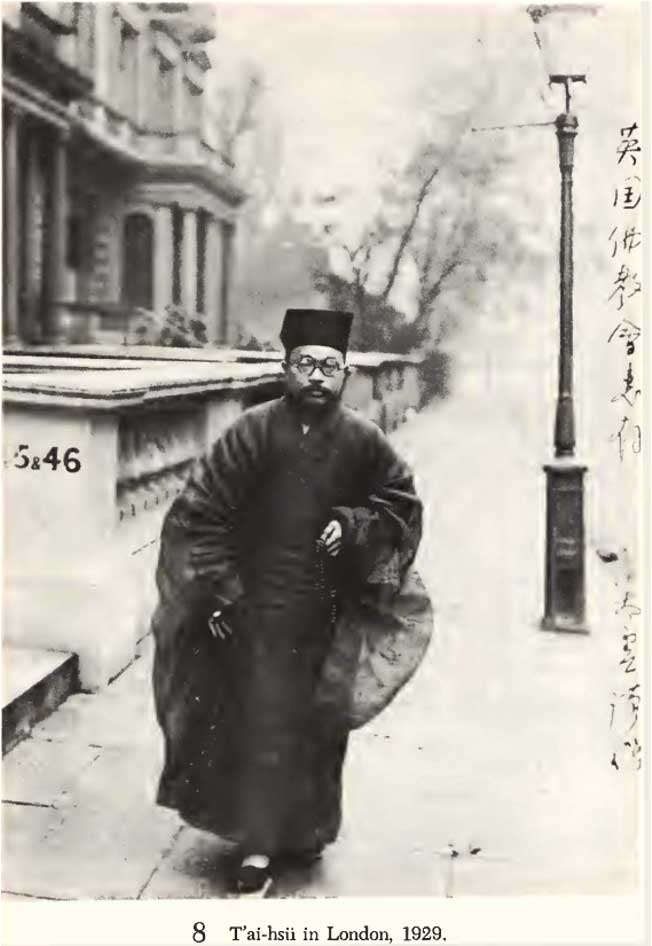

At the center of it all is Taixu (1890–1947), one of the most influential Chinese Buddhist monks of the 20th century. Taixu is widely known for advocating “Humanistic Buddhism,” calling on monks to engage with society and science rather than retreat into isolation.

Less known is his startling re-reading of the cosmos.

Early Indian Buddhist texts describe a flat world with Mount Sumeru at its center. But by the early 20th century, Chinese intellectuals widely accepted that Earth is spherical and that planets orbit the sun. Many Buddhists simply decided that the Buddha’s geography was not the point.

“Most people said, ‘Buddhism is valuable, but the cosmology isn’t essential. The Buddha wasn’t trying to be an astronomer,’” Van Overmeire said.

Taixu refused that escape route. He insisted that the Buddha was still correct, but in a different way.

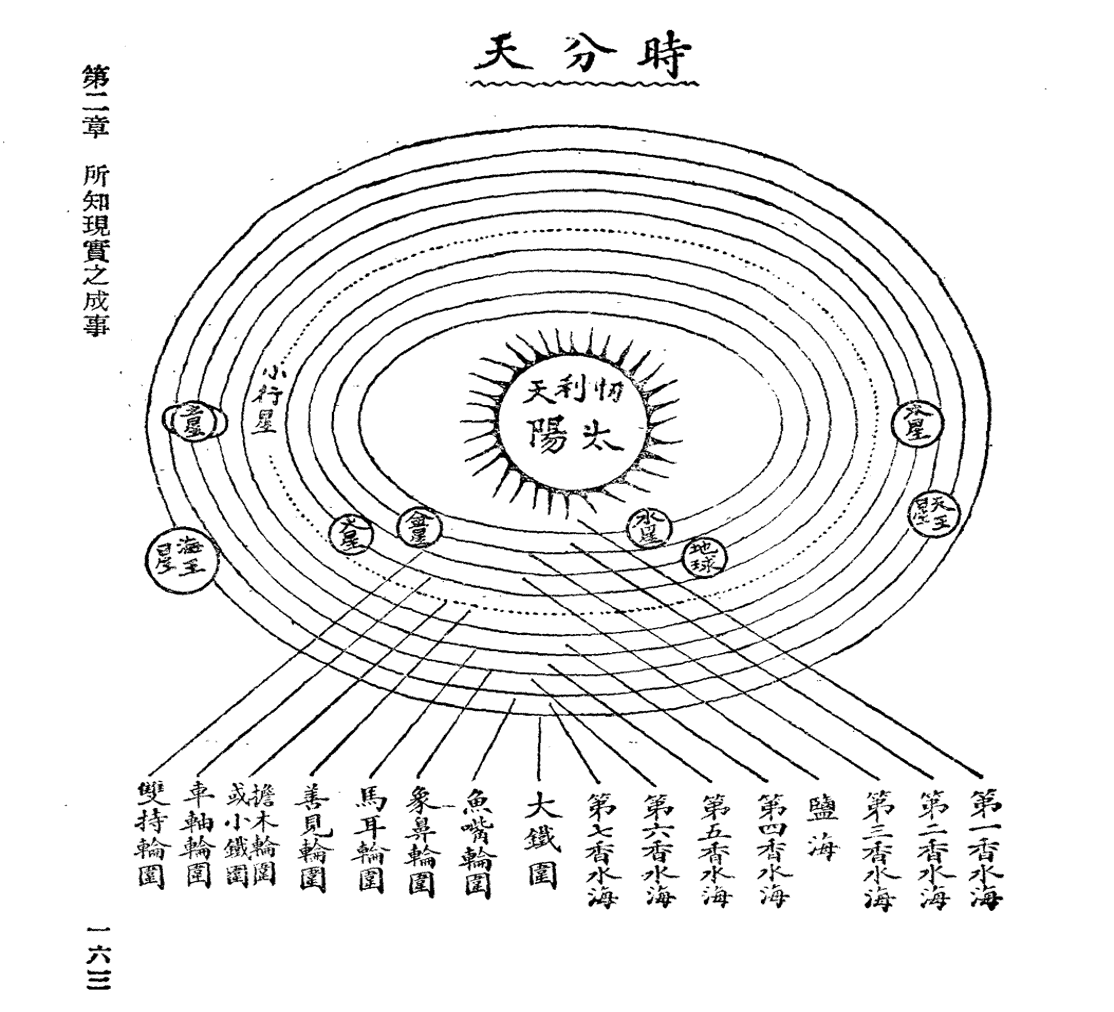

Instead of imagining a literal mountain on a flat earth, Taixu argued that the entire solar system should be understood as Mount Sumeru. In his interpretation, the Buddha had somehow grasped the structure of the planetary system long before modern astronomy.

“For me the question was: why would a very intelligent monk insist on that?” Van Overmeire said. “Why claim that our solar system is a mountain? That’s the puzzle that hooked me.”

Reading Taixu with telescopes and texts

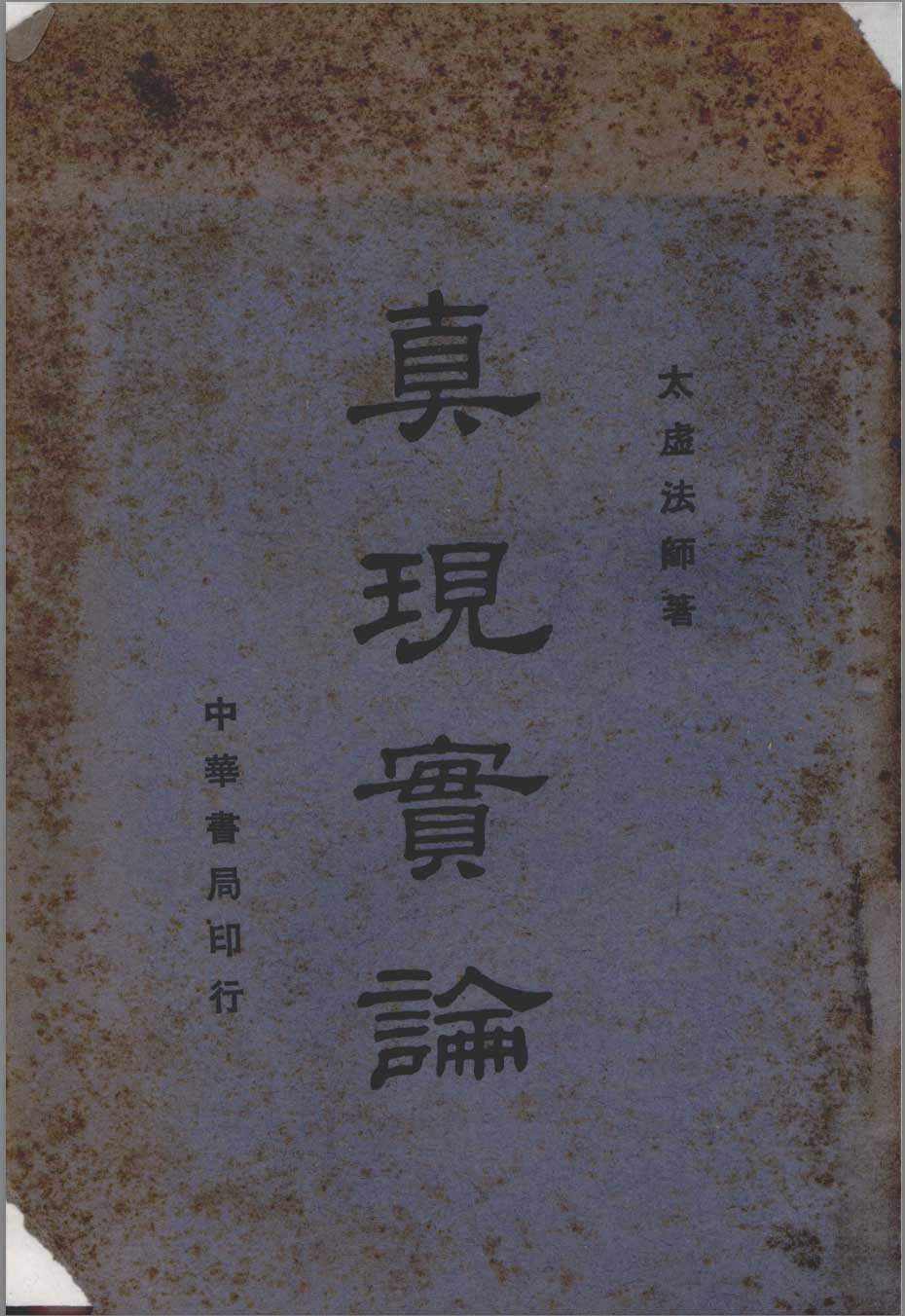

Van Overmeire turned to one of Taixu’s philosophical essays on “true reality.” Written in the early 20th century, the text assumes deep familiarity with Buddhist philosophy, especially Yogācāra theories of consciousness. It is also saturated with references to science, at least the science that was current in the 1920s.

“You can’t read this text with just one pair of glasses,” Van Overmeire said. “You need Buddhist philosophy. You need early 20th-century astronomy. You need evolutionary theory and even social Darwinism. Without all of that, a lot of what he’s doing looks random. But it isn’t.”

Collaborating with Ruixiang Hu, an undergraduate student research assistant, and consulting with generative AI, they produced a draft translation of Taixu’s work from Chinese to English. Then the close reading begins.

“We sit together and ask: what’s weird? What doesn’t fit our expectations?” he said. “Because often, that’s where the interesting things happen.”

Sometimes the puzzle is as simple as a planet.

In one section, Taixu gives unusual importance to Uranus, a planet invisible to the naked eye, unknown in classical Buddhist cosmology, and named in modern Chinese not for the five elements but as the “heavenly king star.”

“From a Buddhist point of view, Neptune doesn’t belong anywhere,” Van Overmeire said. “You can’t see it without a telescope. It has no place in the old elemental system. So why does he care about it?”

Tracing the reference sends the team digging through the history of Western astronomy and astrology, then following those ideas as they arrive in China through translation, popular science writing, and journals edited by figures like Liang Qichao, a leading thinker of early 20th-century China.

A similar detective trail around Mars leads them to the French astronomer Camille Flammarion, whose vivid descriptions of an advanced Martian civilization were widely translated and discussed in early 20th-century China.

The more they read, the clearer the pattern becomes: Taixu is not only reworking Buddhist categories; he is also borrowing and transforming Western scientific fantasies about other worlds.

“From the outside, it looks like just Buddhist philosophy,” Van Overmeire said. “But underneath, you can see the layers of European astronomy, Chinese reform-era debates, and his own creative attempt to make them speak to each other.”

More than rockets and physics

Van Overmeire sees the project not only as historical scholarship but also as a reminder that humanity’s future in space will be shaped by stories as much as science.

When people talk about colonizing Mars today, he notes, the conversation often carries a Christian-shaped storyline, whether consciously or not: Earth is doomed, salvation lies elsewhere, the chosen will leave for a new world in the heavens.

“Elon Musk’s logic—‘this planet is going to destroy itself, so we need to go to Mars to build a new paradise’—is very close to a Christian way of thinking,” Van Overmeire said. “Earth as fallen, the heavens as a pure place. Even if people don’t quote the Bible, the pattern is there.”

China, he thinks, brings a different imagination to space. Look at the names for satellites, space explorers and space stations: Chang’e, Yutu, Tiangong. The missions draw from myth, poetry, and religious imagery, not just engineering.

Taixu’s vision adds yet another layer. He sees the solar system as an organic whole, deeply interconnected, rather than a collection of cold rocks.

“For Taixu, everything is connected to everything else,” he said. “The things you do at your laptop today, he would say, affect the entire cosmos. If we started thinking that way—if we really felt the solar system as our home—wouldn’t that change how we behave, both on Earth and in space?”

He emphasized that modern science still matters, but it does not stand alone.

“Exploring space isn’t just a technical project,” he said. “Our ideas, our ethical frameworks, our religions—they will shape how we treat new worlds, how we respond if we ever meet other forms of life, and whether space becomes just another arena for exploitation.”

A DKU lab for thinking across disciplines

The project also functions as a live laboratory for the kind of education Van Overmeire believes DKU is uniquely positioned to offer.

His student collaborators are not only translating and annotating passages. They are learning to move between disciplines: from Buddhist commentaries to history of science, from AI-generated drafts to conference presentations, from data-sifting in digital notebooks to philosophical debates about consciousness.

“Space exploration as a field is inherently interdisciplinary,” he said. “But that’s also true for a lot of the big questions students will face. You can’t stay inside one narrow lens.”

For him, universities exist precisely to support this kind of work.

“Universities are not companies,” he said. “Their value isn’t measured only by what people will buy tomorrow. They’re the places where you can pursue very niche questions that might turn out to be important later.”

That belief shapes his advice to students, whether or not they ever study Buddhism or space.

“Think broadly,” he told them. “Choose projects and supervisors who stretch you beyond your main field. That’s where the really interesting work often happens.”

As the research group continues to translate Taixu’s essay and present their findings at conferences, Van Overmeire is also drafting a book with the working title Spaced Out: The Buddhist Imagination of Outer Space. One chapter will center on Taixu; others will follow different Buddhist voices in China and beyond as they respond to the arrival of the space age.

Behind the footnotes and the philology is a simple conviction: the stories we tell about outer space will deeply shape what we do there.

“If the only story we have is a space race—a competition to claim territory and escape a ruined Earth—then our future in space will probably be as dark as our colonial past,” he said. “We urgently need alternative visions.”

Taixu, the monk who saw a mountain in the solar system, offers one such vision. His universe is not empty in the nihilistic sense; it is “empty” in the Buddhist sense of radical interdependence.

“You don’t have to agree with his conclusions,” Van Overmeire said. “But his example shows us that scientific data never speaks alone. It always gets framed by stories, values, and metaphors. If we want a better future in space, we need better stories.”

By Chen Chen