Can China innovate? Is there an emerging Chinese innovation model? What role will China play in the evolving global innovation system?

Prominent entrepreneurs, global investors and renowned scholars convened at the Duke International Forum 2016 on the Duke Kunshan University campus May 21 and 22, to discuss and debate these questions critical to driving innovation in China.

The Forum, jointly organized by Duke Kunshan University, Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business and Duke Law School, provided an open platform for the public to learn from the experiences and insights of innovation leaders.

‘There are reasons to believe that China has turned the corner in terms of its innovation system. The recent growth in R&D funding, the nurturing of the new talent, and the new R&D infrastructure in China are starting to yield some meaningful results,’ said Denis Simon, executive vice chancellor of Duke Kunshan University. ‘Based on the comments that came from our panelists, I think we are starting to realize that China has become more integrated into the fabric of the global innovation system. More and more multinational companies are willing to come to China, not for China’s low-cost labor, but primarily for Chinese brain power. China has now become a part of not only the global innovation system, but the global talent pool as well.’

Conference Co-chair Denis Simon Giving Welcome Remarks

Conference Co-chair William Boulding Giving Welcome Remarks

During the May 21 Program for Practitioners, keynote speakers and panelists from BGI, Tencent, J&J China, Tesla, Honeywell, and start-ups in media, entertainment, finance and IT, as well as renowned investors, offered a comparative perspective of China’s role in the global innovation system.

Chinese Innovation: Drivers and Barriers

What is working and what is holding Chinese innovation back? Rao Yi, director of the IDG/McGovern Institute for Brain Research, provided an answer from a natural scientist’s perspective.

Keynote Speaker Rao Yi

As he noted, ancient Chinese preferred to pour their creativity into writing and developing practical technologies instead of scientific research. Unlike the United Kingdom, Germany or the Soviet Union, China has little tradition in science. ‘Only after the Opium War in 1840 did the Chinese realize as a nation that there were huge gaps in science with their Western counterparts to catch up with. So in China, primary schools and middle schools were reformed only after 1840s, and universities were established only after or around 1900. Most scholars went to Britain, Germany, Japan and the U.S. for education, and then brought back textbooks and translated them. The research output over the last a hundred years has been very sporadic at best.”

Rao also applauded China’s recent efforts to boost funding for scientific research. He pointed out that the increased funding has allowed Chinese scientists to be more innovative. ‘In the natural sciences, there is great freedom for Chinese scientists to do original research because there are fewer restrictions on funding.’

Experienced business leaders, including former Chairman of Johnson & Johnson China Jesse Wu, , Southeast Asia President of Honeywell Briand Greer, and General Manager of Tesla Motors Tom Zhu, were also bullish on Chinese innovation.

Keynote Speaker Jesse Wu

Keynote Speaker Wang Jian

Keynote Speaker Tiger Sheng

‘There are three critical factors driving the development of healthcare innovation in China,’ said Wu. ‘First, China’s significant demand for innovative healthcare solutions; second, the government’s firm commitment to supporting innovation in general and healthcare innovation in particular; third, the growing levels of financial and human capital invested by the private sector.’ He also suggested that adopting a more global standard would help Chinese pharmaceutical companies shift their strategies from ‘in China for China’ to ‘in China for the world’.

Jesse Wu’s emphasis on standardization was shared by Briand Greer and other entrepreneurs. Greer said that in the aerospace industry, technology is not the issue for China. ‘The biggest problem we see is not about technical expertise, but more around system integration.’ As Greer noted, if Chinese companies want to ‘play in the Western world’, there should be policies that can drive them to design airplanes from a Western perspective.

Panel Discussions #1

Having been working with innovators from the U.S., Israel and Germany for many years, Wang Ou, managing director of Private Equity Investment, China Investment Corporation, made a careful comparison of the different innovation models of Silicon Valley, Germany and Israel, and concluded that ‘innovation is not unified.’ ‘When you deal with different innovations, you are actually dealing with different cultures, different people, and different histories,’ he said.

Panel Discussions #2

Fostering Entrepreneurship in China

To boost employment and sustain growth, China has rolled out new policies to encourage innovation and entrepreneurship. At the same time, concerns have been raised about whether entrepreneurship is the right model for innovation in China.

According to Lynn Yang, managing director of Sequoia Capital China, the percentage of first-class technology innovation projects in China is growing very fast. ‘Quantitative changes can lead to qualitative changes, and we have spent at least 20-30 years to have the whole society improved. China now has not only the dream, but also the capability to innovate.’

Panel Discussions #4

Derrick Xiong, co-founder & CMO of Ehang, is also optimistic about the idea of mass entrepreneurship and innovation. ‘China is a country that is growing so fast, and there is a huge space for entrepreneurs to fill in.’ He added, ‘China has a higher tolerance for risks compared to other countries, and is still one of the best places to start a company.’

Given that protection of intellectual property is another key to fostering innovation, Professor Gao Xiqing from Tsinghua Law School reviewed the history of the establishment of Chinese patent law, and said that China must respect intellectual property rights if it wants to encourage innovation.

Kenneth Jarrett, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai, added that China’s effort to enhance protection of intellectual property would motivate multinational companies to increase their investment in research and development in China.

Panel Discussions #3

Science, Technology, Talent and Innovation

Over the last decade, China has engaged in a sustained effort to become more innovative and shift its products from ‘made in China’ to ‘designed in China.’ These efforts seem to have achieved considerable success ‘ China now ranks 1st world-wide in patent filings according to the WIPO, and according to a 2013 report by KPMG, is home to over 1,300 R&D centers operated by multinationals, including more than 400 operated by Fortune 500 companies. Collectively, the country now accounts for 43% of new Global R&D spending. A first-pass reading of these headline figures would suggest that China has become both a key market for every leading company’s products and services and increasingly, a hoped for source of innovative ideas for those products and services.

But is this reading an accurate one? Have recent reforms in science & technology provided the necessary new glue to help overcome the barriers to becoming more innovative? To what extent are China’s international science &technology linkages paying off? How strong is China’s talent pool?

To help address these questions, the second day of the two-day forum provided a roundtable for senior scholars and researchers to discuss issues related to talent and S&T development in China.

Roundtable Speaker Cao Cong

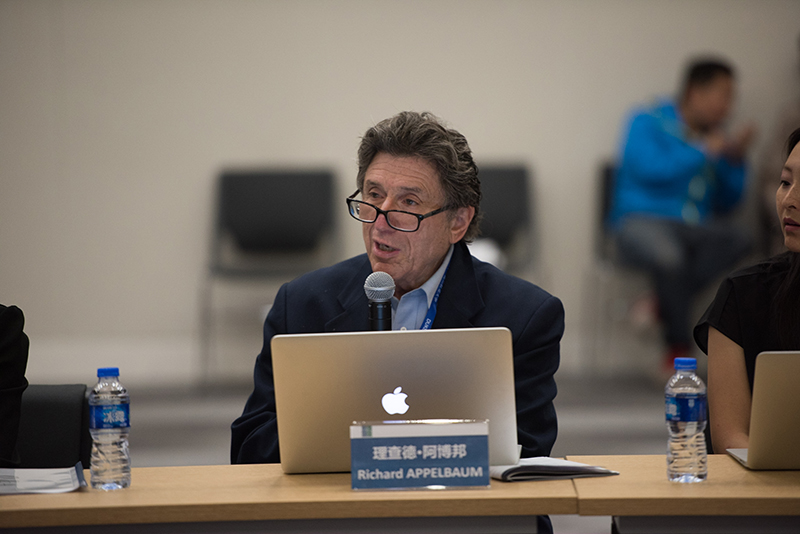

Professor Cao Cong from University of Nottingham Ningbo mainly discussed several major talent challenges China faces at the moment, including demographic challenges, historical challenges, and the ‘brain drain’ challenge. According to his research, the number of Chinese students pursuing an undergraduate degree in the U.S. has skyrocketed since 2006, and those who went to the U.S. for high-school or undergraduate education are often not well prepared for starting a career in China. Instead, they are more likely to stay in foreign countries after graduation. In addition, according to Professor Richard Appelbaum of UC Santa Barbara, many returned scientists have run into organizational and cultural obstacles after returning to China, leading to frustration and unmet expectations.

Roundtable Speaker Richard Appelbaum

Dr. Mu Rongping from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Dr. Denis Simon from Duke Kunshan University drew on their own experiences to offer Chinese universities advice on partner selection for international scientific collaboration. ‘Chinese universities seldom work with universities from non-English speaking countries,’ Mu said. ‘Sometimes they pick a partner university that is not their best fit.’ Denis Simon added that false expectation that result from misunderstanding can also lead to problems in international S&T collaboration.

Roundtable Speaker Mu Rongping

Denis Simon added that while many cooperation agreements have been signed, the reality is that many of the foreign and Chinese partners have been disappointed in the results; the disappointment derives from strategic and operational misunderstandings that yield suboptimal results from misaligned efforts during cross border collaboration. Chinese and foreign universities need to identify better matched partners in terms of academic culture and organizational decision making so they don’t waste time, resources, and valuable opportunities.

Roundtable Speaker Denis Simon