By Ge Gao

Staff writer

Global awareness of the causes and consequences of depression have never been greater. Recognition of the mental illness has aided both diagnosis and mitigation, while modern research, such as the recent work by Duke Kunshan biologist Chang Y. Chung, is helping to identify the root causes of depression in the human brain, potentially opening the door to preventative therapies.

However, such awareness is relatively new. To mark World Mental Health Day, which fell on Oct. 10, we look at the perception of depression through different periods of history.

Earliest accounts: Demons and evil spirits

The earliest written accounts of the symptoms now associated with depression ‘ fatigue, longer-term sadness, and intense feelings of helplessness ‘ appeared in Mesopotamia in the second millennium B.C. Similar symptoms were discussed in ancient Chinese, Palestinian, Egyptian and then Babylonian texts, too.

Knowing little about natural science, the ancient Aztec and Inca civilizations believed that all illness was a punishment from the gods, while the Assyrians and Babylonians regarded diseases as demonic phenomena. As a result, exorcism was the predominant method of treatment for depression. In the New Testament, Jesus also performs exorcisms on the mentally ill to demonstrate his miraculous powers.

Saints ‘ and objects carried or touched by saints ‘ were also seen to have healing powers. St. Bede, writing in ‘The Ecclesiastical History of the English People,’ recounts that the Benedictine Monastery was clueless about how to cure a patient ‘possessed by evil spirits.’ In the end, the abbot ordered a casket filled with the soil that St. Oswald had touched when he fell. When the casket arrived, the patient’s depression miraculously improved.

Ancient Greek and Roman philosophy

Greek physician Hippocrates, regarded by some as the father of medicine, was the first approach depression with rational thinking, in the late fifth century B.C. He was dismissive of miracle cures and suggested that depression was an imbalance in the body’s four humours: yellow bile, black bile, phlegm and blood. Too much or too little of any humour would lead to illness or even change one’s personality traits.

Specifically, Hippocrates thought that depression resulted from too much black bile in the spleen, which explains why depression was known originally as melancholia, derived from the Greek word melainachol, meaning black bile. He proposed treating the condition by regulating the four fluids through bathing, bloodletting, exercise, dieting and herbal remedies.

The first record of depressive symptoms was by the Greek physician Aretaeus of Cappadocia, who practiced in Rome and Alexandria about 500 years later. In his text ‘On the Causes and Indications of Acute and Chronic Diseases,’ he describes in detail the symptoms of a patient supposedly inflicted with depression: ‘The patients become peevish, dispirited. They are unreasonably torpid, without any manifest cause: such is the commencement of melancholy. If the illness become more urgent ‘ hatred, avoidance of the haunts of men, vain lamentations; they complain of life, and desire to die.’

However, philosophers at the time had a different view. Socrates and Plato believed that serious mental illnesses, including depression, stemmed from unusual childhood experiences. In a similar vein, centuries later, Roman philosopher and statesman Cicero believed that melancholia had psychological causes such as rage, fear and grief.

The Middle Ages and the Renaissance

In the Middle Ages (circa 476 to 1450), when theocracy was prevalent, depression and other mental illnesses were seen as a moral failing. Thomas Aquinas, the theologian, argued that the soul was not subject to the corruptibility of physical illness; he believed the mentally ill were possessed by the devil, demons or witches, or had lost God’s blessing.

Treatment included flogging, starvation, immersion in water and imprisonment. In extreme cases, the sick were tortured to death as witches or heretics.

A relief at the Cathedral of St. Trophime in Arles, France. Photo by Falco / Pixabay

While ignorance loomed over Europe, in ninth-century Persia, physician Rhazes spoke of the brain as the ‘seat of mental illness.’ In addition to recommending traditional cures such as hydrotherapy and herbal remedies, he also used early forms of behavioral therapy, such as rewarding appropriate behavior.

When the Renaissance (15th and 16th centuries) spread throughout Europe, views on depression took another turn. The fashion in high society favored a pale complexion, a sad countenance and furrowed brows, all indicating indifference to the world. The aristocrats, courtiers and literati believed that melancholy meant nobility, depth and talent, and men and women would copy the mannerisms of melancholics.

Apparently, the trend was not for everyone, though. When a 16th-century barber complained to his neighbor that reading ‘Hamlet’ had sent him into deep melancholy, all he received in reply was a sneer: “Melancholy? How dare you a barber speak about melancholy? That’s like the coat of arms only courtiers are entitled to wear.’

The Age of Enlightenment: Return to rational

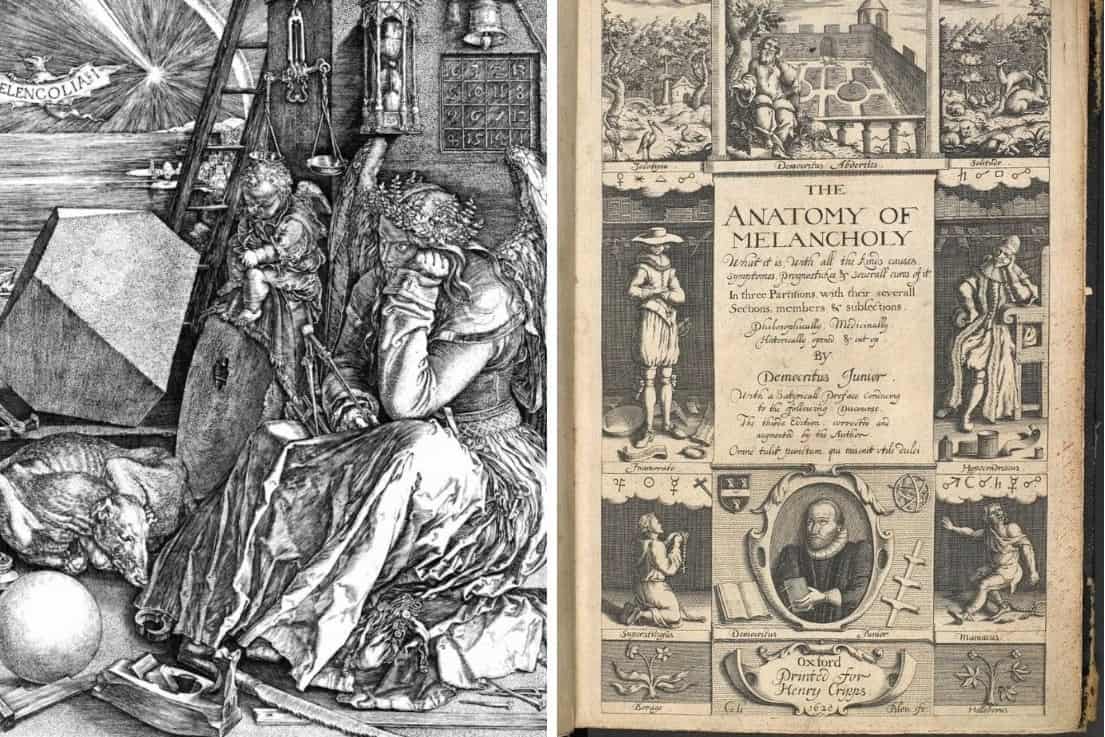

Along with growing interest in natural sciences, some doctors in the Age of Enlightenment (17th and 18th centuries) took Hippocrates’ view that mental illnesses were due to natural causes, not demonic possession. The most influential figure was Robert Burton, who in ‘Anatomy of Melancholy’ detailed several psychological and social causes of depression, including poverty, fear and loneliness. He recommended some old and new treatments, such as travel, diet, exercise, purgatives and music therapy.

In keeping with the Industrial Revolution (circa 1760 to 1840), some medics viewed the human body as a machine: A malfunctioning part just needed repair. Some believed the cause was misplaced brain contents and advised the patient to sit on a spinning stool to put the contents back into their correct position. Others blamed a loss of elasticity in the body’s fibers, so would immerse the patient in water for as long as possible without drowning him or her.

During this time, Benjamin Franklin, a founding father of the United States, is said to have developed an early form of electroshock therapy for depression and other mental illnesses.

The 19th century

Romanticism and research in the 19th century brought to the world a different perspective on depression. Historians found that many gifted men and women throughout history had mild, moderate or severe depression.

Isaac Newton wrote of his anxiety, sadness, fear, low self-esteem and suicidal thoughts between 1666 and 1691, while Beethoven believed that we ‘poor but often happy humans’ seemed to switch between only two moods: Happiness and sorrow. Charles Dickens and Vincent Van Gogh, who died by suicide, also were recorded by people close to them as having recurring symptoms of mania and depression.

Left: ‘Melencolia I’ (1514) by Albrecht D??rer. Right: Robert Burton’s ‘Anatomy of Melancholy.’

With this new view of melancholy as the origin of creativity, ‘being depressed’ became somewhat fashionable again. At the same time, melancholy was seen as a hard-won inner peace between the two fast-paced industrial revolutions. German philosopher Immanuel Kant believed that ‘melancholy is a refuge from the hustle and bustle of the world.’

Fortunately, research on depression continued regardless of the change in perception. In 1895, Emil Kraepelin, the founder of modern psychiatry, distinguished three clinical varieties of depression: Catatonia, in which motor activities are disrupted; hebephrenia, characterized by inappropriate emotional reactions and behavior; and paranoia, characterized by delusions of grandeur and persecution.

Kraepelin was the first to make the distinction between manic-depressive psychosis and dementia praecox, known today as schizophrenia. Manic-depressive illness, or bipolar disorder, which is characterized by dramatic changes in mood, affected well-known figures including Newton and ‘Gone with the Wind’ actress Vivian Leigh.

The research has had a lasting and significant contribution to the way we understand depression today.

‘We’ve really come far in our awareness of depression and other mental illnesses, but there’s still some way to go,’ said Yan Li, director of Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) at Duke Kunshan.

‘Depression affects about 260 million people worldwide, and while many are receiving help, others are suffering in silence,’ she said. ‘We need to work together to provide more support services and encourage people to reach out to those who can help.’

Duke Kunshan students who would like to discuss issues of mental health can contact CAPS on caps@dukekunshan.edu.cn. CAPS provides face-to-face and virtual counseling services.